Peace is an Attitude: Seeing into the Invisibles

Dennis Patrick Slattery, Mythological Studies Program

Peace has a purpose but it is an enormous topic as well as a complex feeling and attitude toward self and the world. Rather than treat it conceptually, I want to share an experience that I had years ago while pilgrimaging for three and a half months when I stayed at various monasteries and zen centers in the Western United States. See this as a vignette that I hope touches with some insight the development of inner peace, the only locale where it must, to my mind, take place and grow before any change in the world is to take place. In my pilgrimage I found peace most deeply and most frequently on my walks and meditations in the natural order. Perhaps that is where many of us need to begin.

At one monastery in Oregon, I found in their tape library an arresting talk by the monk Brother David-Steindelrast, a writer whose work I know from reading. Listening to him was a very different and far richer experience. So let me begin with that, then take you outdoors with me where something of peace’s profound presence entered me.

Brother David’s voice was animated, vibrant, emotional and joyful; I enjoyed his style as he outlined the qualities he believed constituted meditative prayer: wholeheartedness, leisureliness, faithfulness, authenticity and gratefulness. All of these qualities involved the heart rather than the head; the heart, he suggests, stands for the whole person, the deepest root where a person is of one piece, the realm where one exists with self, others, and God. A God experienced in the heart constituted for him the ultimate reality. All of us, he claims, are made for happiness; this condition grows directly from discovering and creating meaning in our everyday lives. Religion is the human quest for ultimate meaning, “so the term ‘God’ is not necessary” (A Practical Guide cassette tape). There are, for Brother David, many deeply religious atheists in the world also searching for meaning.

His idea of the difference between free time and leisure was helpful and encourage me to continue the quest; on my pilgrimage I had an abundance of free time, but it was not a synonym for leisure. Leisure “is to allow time to work for its own sake wherein I allow myself to be open to what is happening right now” ( A Practical Guide cassette tape). This leisurely attitude is a virtue because it allows one to give it time and to take time. The heart in its rhythmic beating continually pumps and rests, pumps and rests. It gives and takes, gives and takes, and so it is the best model for leisure’s rhythm: a constant give-and-take in time.

Our lives and vocabulary, Brother David revealed, is full of “take” language with very few “give” responses. For example, I take a test, a seat, a nap, a vacation, time, a shower, and a drink. Some despondent souls, reaching for a solution that eludes them, may even “take” their own lives because they cannot not “take it” anymore. Our learning must include the word “give”: to give ourselves, to give over to . . . to give in. Giving in, giving ourselves over to God, giving up old habits–“dead branches” he calls them–can help us incorporate the “give” back into the “give-and-take” of life to restore the heart’s rhythm.

Brother David’s simplicity in such a profound meditation stirred my own heart, giving it more time to make me aware of its rhythm. And then his punch line on for-give-ness (as opposed to always taking-offense, which was one of the most destructive forms taking can, well, take). For-giving, by contrast, is one of the most generous forms of giving. Christ, he suggests, took on the sins of humanity and for-gave them. Christ was the fullest model of the give-and-take of suffering and forgiveness, the great gift-giver. Grace was a given; it was freely given to us as a gift. We can take it or shun it. Somewhere I recalled here that it is better to give than to receive, to give rather than take.

Grace may then be God’s way of showing us a gift without measure; we can choose freely take it, accept it or reject it. Our choice would determine how we entered into this give-and-take relationship with God. I thought too of Meister Eckhart’s writings on compassion. Forgiveness is one of the highest expressions of compassion. In compassion we give—or for-give; in consuming we take. How to allow compassion to replace consuming was a large challenge for me, one which I wished to transform into action.

I “took” his thoughts with me next day when I drove north of Portland to Souvie Island where I “took” a hike along the Columbia River on a beautiful cool sunny day, a gift God had “given” me without conditions. I watched enormous cargo ships glide up the river as I hiked to a lighthouse, through the forest and through herds of cattle that made me skittish. These cud chewers looked at me suspiciously from above rheumy noses. I climbed a fence and walked gingerly by two bulls that suspected me of having an eye on their hefty harem. I tried to appear deferential, to give them a clear sense that these beautiful cows were just not my style.

I observed and moved within such a welcoming natural terrain with new eyes. It was a revelation to see throughout nature how the living and the dead existed side by side and how new life sprang from the decay of old matter. Some clotty soil suddenly let go along the bank of the river and slipped into the flowing stream. Motion and stillness, give and take, new life from old—the patterns continued to surface and I sensed that what had been invisible to me for so long was now revealing itself. All is revelation, all is relation, all is realization. The leaves, covered with dirt, reentered the earth, having fallen from great heights. It was fall and all was falling, returning to the earth and participating in an ancient cycle. Many of them already crispy brown, returned to replenish the soil for next year’s growth.

As I walked, a leaf, acting very forward, spiraled down and landed on my cap. It wanted a last horizontal ride before finally falling on to the bank of the river. I obliged it. Water spiders jerked in joy along the slick calm liquid surface as the Columbia River, deep and silent as God’s presence in the stream of my own life, flowed without a ripple. We are each given a certain amount of time on this earth; we can spend that time taking or giving or combining the two. To give of one’s time or person to another is one of the great gifts a person can bestow. It such a generous act, one is repaid with the presence of peace. Perhaps I must take the time to give it.

Leaves that had fallen into the water floated along the top, while each shadow followed and mirrored in shadowy similitude its twin floating along the shallow water close to shore. Dead logs and branches lined the muddy bottom. Leaves quietly hosted the sun, palms gently facing out. A leaf bobbed and weaved its meandering descent into the river. Sounds began to increase under the thick bushes to my left. A spider’s web caught the sunlight in its gentle sway, and for just an instant, out of the corner of my eye, I noticed the filaments of perfect symmetry. This scene was too delicious to pass by, so I sat for a moment on an adjacent log to enjoy the patient and confident engineering of the web, still wet from last night’s moisture.

This doubling of nature awoke in me the belief that I—each of us—was a double of God, a double of divinity; that what took place in the visible order was duplicated in me in a divine way. I waited for these instants of insight in the natural order, where God spoke quietly but clearly, if only I had the eyes and the ears to take it in by giving myself over to God’s conscious presence.

Then, as I gazed at the web, it suddenly disappeared. For a moment I thought I had hallucinated it. But the sun’s light had shifted just a shudder to the right to make it disappear. I knew the web was right there, almost where I could reach and touch it in its invisible presence between the two small shrubs to which it was anchored; an invisible presence now, yet I knew its existence was a matter of inches from my face. How many other webs were right in front of me, which I did not see because the attitude of the light, or because my angle of vision blinded me to them. I recalled once again a physicist’s belief that we have visible to us only about four percent of the created order. The rest is hidden in not so plain view.

OK, but there are moments, like this one, as I shifted my position mere inches on the log, when again the spider web appeared to me as the sun once more caught it to make it magically visible to sight. So it must be that we can, depending on our disposition, see parts of the universe that may become visible when we are seated correctly or find the right angle or the appropriate attitude for their appearance. It needn’t move, but I must be willing to. I thought that this phenomenon could also reveal God to us through moments of grace, if grace were understood as a gift by which we are given an angle of vision of God. Grace may be thought of as a light which, when slanted in the right attitude, reveals what is invisibly before us, pulsing its own reality, daring to be seen by anyone with sufficient grace to see. I felt welling up in me a gratitude inspired by grace and the gift of the imagination to be aware of what is now invisible, now visible a give and take of dimensions of reality going on all the time. This, I thought, is what poets write about: those instants of vision when the light catches the invisible and allows the full measure to be seen for a moment in time.

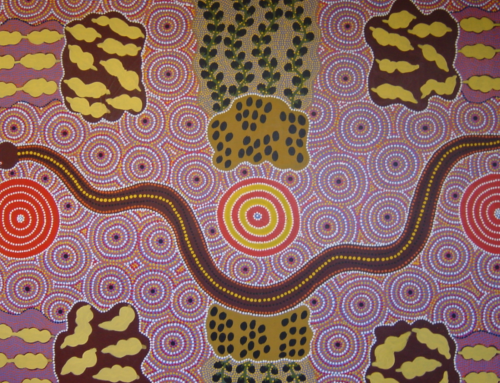

Sitting alone on a log next to the deep flow of the Columbia River contemplating a peek-a-boo spider web and delighting at how little prompting I needed to enjoy the mystery of the world, I felt the absence of any boundary existing between the physical and spiritual realms, between the natural order and supernatural presence, between the world’s tangible body and its invisible gracefulness, between time and eternity. It was an instant of grace, freely given and gratefully taken; I found myself in the thick of the give-and-take of creation. All the low points, the loneliness, the feelings of depression, of sadness of grief, of emptiness, of loss, of wanting to head home, evaporated in the face of this spider web, which had once more playfully disappeared. Its ability to remain on the margin between visibility and invisibility was its strength like the eyes of the insects it wanted to ensnare were so multi-faceted and keen that only a web that could disappear would ever snag them. This web’s presence, when perceived, was akin to the effects true praying and authentic poetry had on the senses. Both of them made visible what was hidden in plain view, just in front or next to us or coming up from behind. Our failure was in lacking the right attitude by which to see it. I believe more strongly now that it requires an attitude of peace, of serenity and of acceptance of what is to coax the invisibles into presence.

Both prayer and poetry make visible what is hidden in plain view, just in front of or next to us. My weakness was not having the right attitude by which to see it. I shifted my position to defer to this reality.

Zen Web

The spider’s mandala

rests serenely anchored like a large enmeshed

wheel between two scrub bushes linking forest

and river.

The sun gives it shape and an angle of clear vision.

It vanishes when the sun blinks behind

a swaying leaf.

The spider rests zen-like at the center, in perfect

zazen, waiting, praying, proud of its design it

spun from a memory it did not recall it had.

Only when the web fades, becomes clear

force, does the spider move wavily in mid-air

above the ground towards a small moth

flapping against the sticky filaments of zazen.

Two scrub bushes, keeping the tension of the moth

between them, bow slightly towards one another.

Buddhists of the forest embrace the flame of death.

Developing an attitude of peace in our daily lives places us finally in the intimate space of death. Knowing our mortality, our woundedness, our frailty and imperfections can enhance, not detract from cultivating an attitude of peace and forgiveness towards oneself and others. Then the world can indeed change for the better.